The intersection of gender, perception, identity, and space have, for centuries, collided to illustrate a skewed depiction of Arab women. The art of Orientalism brought about imagined scenes of women in harems, hidden in seclusion behind veils and walls. As these images continue to shape Western perception of Arab women, Moroccan-born artist, Lalla Essaydi, reclaims and deconstructs these images. In her exhibit, Lalla Essaydi: Revisions, at the Smithsonian National Museum of African Art, through her experiences as an Arab woman living in the West, she presents her past.

Samia Errazzouki (SE): What themes does your show Lalla Essaydi: Revisions at the Smithsonian National Museum of African Art focus on, and how are they reflected through the title?

Lalla Essaydi (LE): The Revisions exhibition is about revising stereotypes and it is the first solo exhibition to bring together works of diverse media. In that holistic context, they display the depth of my engagement with different media, art historical conventions, and diverse cultural histories, as well as my technical mastery of composition and color. It is a retrospective.

SE: How does your work pose questions about gender, identity, and space?

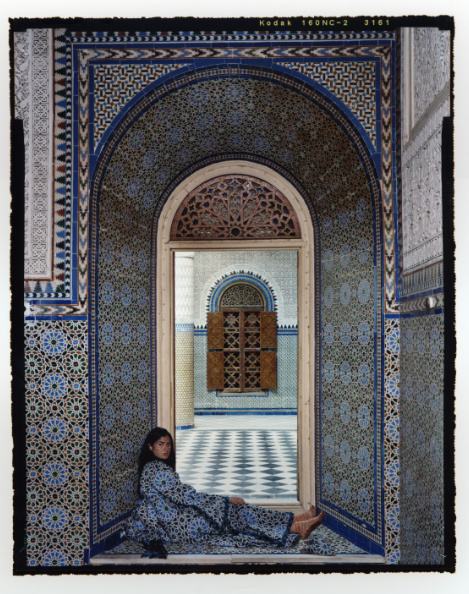

LE: My work is haunted by space, actual and metaphorical, remembered and constructed. My photographs grew out of the need I felt to document actual spaces, especially the space of my childhood. At a certain point, I realized that in order to go forward as an artist, it was necessary to return physically to my childhood home in Morocco and to document this world which I had left in a physical sense, but of course, never fully in any deeper sense.

Women’s sexuality, in the Arab world, has determined the very nature of public and private space. Arab women traditionally occupy a private space, but wherever a woman is, when a man enters that space, he establishes it as public. This separation of public and private is testament to the power of women’s sexuality. It also helps explain how Arab women became sexualized under a Western gaze. In a sense, what the West did was to dissolve the boundaries between public and private, and—here is the important point—the Arab world responded by reinstating those boundaries in a way that would be clear and visible. Behind the veil, an Arab woman maintains a private place, even in public.

SE: Calligraphy has a history of being a substitute for figural representation in Islamic art. What role does calligraphy play in your art?

LE: When I was growing up, calligraphy was not included in the school curriculum, although it could be studied via a private tutor. It has only recently been introduced in Moroccan art schools. I personally have no training in calligraphic art, and approached it as an artist would approach any new artistic medium, attaining skill through practice. I have developed my own method of transcribing my calligraphic text—applying henna via a syringe. The text is written in an abstract, poetic style, so that it acquires a universality which reaches beyond cultural borders. But the text inscribed on the women is deliberately indecipherable, invented forms that allude to kufic calligraphy, but yield little direct access to information. Thus the interplay between graphic symbolism and literal meaning, as well as the European assumption that the written holds the best access to reality, are constantly questioned.

In my mind, since calligraphy, poetry, and architecture are considered high art in Islamic Art as it could be seen though art history, I use it to reclaim the rich tradition of calligraphy and interweaving it with the traditionally female art of henna. I have been able to express, and yet, in another sense, dissolve the contradictions I have encountered in my culture: between hierarchy and fluidity, between public and private space, between the richness and the confining aspects of Islamic traditions.

[Harem #14C by Lalla Essaydi. Image provided by artist]

SE: How have your experiences both in the Middle East/North Africa and the West shaped your perspective as an artist?

LE: As an Arab artist, living in the West, I have been granted an extraordinary perspective from which to observe both cultures, and I have also been imprinted by these cultures. In a sense, I feel I inhabit (and perhaps even embody) a “crossroads,” where the cultures come together—merge, interweave, and sometimes clash. As an artist, I am inhabiting not only a geo-cultural terrain, but also an imaginative one. This space continues to define itself, to unfold and evolve, and as an artist, I feel it is my job (and my passion) to try and understand it, and to make work that flows from this continuing investigation. The different space I inhabit in the West is a space of independence and mobility. It is from there that I can return to the landscape of my childhood in Morocco, and consider these spaces with detachment and new understanding. When I look at these spaces now, I see the two cultures that have shaped me and which are distorted when looked at through the "Orientalist" lens of the West.

SE: What do you seek to do by reproducing the “exotic” and “mysterious” depictions of Arab women from Orientalist harem art?

LE: I am not “reproducing” the “exotic” and “mysterious” depictions of Arab women from Orientalist harem art. I am deconstructing these paintings by using the same stereotypes one finds in these paintings.

My work reaches beyond Islamic culture to include the Western fascination, which we see so powerfully in painting, with the odalisque, the veil, and the harem. It’s obvious to anyone who cares to look that images of the harem and odalisque are still pervasive today, and I am using the female body to complicate assumptions and disrupt the Orientalist gaze. I want the viewer to become aware of Orientalism as a projection of the sexual fantasies of Western male artists, in other words, as a voyeuristic tradition, which involves peering into and distorting private space.

SE: Given the growing exposure of your artwork to a Western audience, what role would you like to see your work have as a part of the discourse on Arab women?

LE: It is my hope that this strategy will make viewers aware of their expectations—i.e, of a certain sexual content—found within the orientalist paintings, by confusing these expectations. The result will be to throw viewers back on themselves, so that they begin to see the dynamics of the Orientalist gaze.

But, by invoking the Orientalist tradition in a way that makes the viewer aware of its inherent assumptions, I hope not to provoke some kind of “blame game” but rather to liberate viewers—Arab and Western alike—from the grip of these assumptions. Furthermore, I am not a sociologist, I am an artist, working from a particular vantage point, and as such hope to give full expression to a uniqueness that I hope will resonate with the uniqueness of each viewer.

[Lalla Essaydi’s exhibit, Lalla Essaydi: Revisions, will be at the Smithsonian National Museum of African Art until 24 February 2013. Read more about Lalla Essaydi here]